This film seems to occupy a zone at the borders of a lot of different genres. Of course it is a vampire movie, complete with an ancient creature, Marguerite Chopin, with dark powers, corrupted minions, pale and suffering female victims, and an earnest young man appalled but also fascinated. In this instance the well dressed young man Allan Gray (Julian West)—he’s always wearing a tie—arrives as things are falling apart. Fueled by a sense of dread, as the intertitles inform us, Allan wanders all over the manor on the bright moonlit nights. He sees the shadows of people digging, arguing, and dancing, he sees disturbing glimpses of ominous things, and even the ordinary things about the place take on a tone of ominousness. At one point he becomes insubstantial, his transparent hand opening a door. He sees himself in a coffin with a little window, and then we see as he would see from inside, the peg-legged soldier screwing down the lid, the vampire peering in, a candle burning and melting. There are scenes of chasing, of rowing a boat in the fog, of Allan staring incredulously at the dying father, the anemic daughter, the manifold strangenesses—all this suggests the work of Man Ray and people like that, rather than than a traditional vampire narrative. After reading the book the father has left behind for Allan, the elderly handyman goes off to the churchyard to drive a stake through the monster's heart, and Allan helps. The body in the coffin turns to bones, the peg-legged soldier falls downstairs, the wicked doctor is suffocated with flour in the mill, the anemic woman is revived, and her young, wide-eyed sister and Allan go running through the woods toward the light –the emblematic happy ending. A goo

This film seems to occupy a zone at the borders of a lot of different genres. Of course it is a vampire movie, complete with an ancient creature, Marguerite Chopin, with dark powers, corrupted minions, pale and suffering female victims, and an earnest young man appalled but also fascinated. In this instance the well dressed young man Allan Gray (Julian West)—he’s always wearing a tie—arrives as things are falling apart. Fueled by a sense of dread, as the intertitles inform us, Allan wanders all over the manor on the bright moonlit nights. He sees the shadows of people digging, arguing, and dancing, he sees disturbing glimpses of ominous things, and even the ordinary things about the place take on a tone of ominousness. At one point he becomes insubstantial, his transparent hand opening a door. He sees himself in a coffin with a little window, and then we see as he would see from inside, the peg-legged soldier screwing down the lid, the vampire peering in, a candle burning and melting. There are scenes of chasing, of rowing a boat in the fog, of Allan staring incredulously at the dying father, the anemic daughter, the manifold strangenesses—all this suggests the work of Man Ray and people like that, rather than than a traditional vampire narrative. After reading the book the father has left behind for Allan, the elderly handyman goes off to the churchyard to drive a stake through the monster's heart, and Allan helps. The body in the coffin turns to bones, the peg-legged soldier falls downstairs, the wicked doctor is suffocated with flour in the mill, the anemic woman is revived, and her young, wide-eyed sister and Allan go running through the woods toward the light –the emblematic happy ending. A goo d deal of the film is beautifully shot, using experimental techniques. Another odd thing is that the film has a sound track, with scary music and sounds, but there’s not a lot of talking and a lot of scenes involve lengthy close-ups of faces changing expression, and so it feels a lot like a silent film. And because so much of the film is mediated through Allan, whose dream it is, there’s not really so much scariness.

d deal of the film is beautifully shot, using experimental techniques. Another odd thing is that the film has a sound track, with scary music and sounds, but there’s not a lot of talking and a lot of scenes involve lengthy close-ups of faces changing expression, and so it feels a lot like a silent film. And because so much of the film is mediated through Allan, whose dream it is, there’s not really so much scariness.

A thirteen-minute experimental film made in Los Angeles by Maya Deren (née Eleanora Derenkowsky) and Alexander Hammid. The film is an unusual hybrid of surrealism, Freudian symbol, and art photography—as if Martha Graham and Luis Bunuel had collaborated on a project with an accomplished photographer who’d just been given her first movie camera. Actually, Deren had really just purchased a 16mm Bolex camera, and she and Hammid shot the film together. There is no plot, naturally, for the images and sequences recur, sometimes with variations, as do the symbolic set-pieces. The woman sees a tall, hooded figure with a mirror instead of a face and she follows it out of her house and along a summer street. She enters a room, sees the figure carry a large flower up some stairs and drop it on the bed. Or she is at home asleep in a chair. The figure is walking away as she watches it—and herself following—from the window. She takes a key from her mouth. She finds a butcher knife and carries it around. She is asleep. She is running. She enters a room where she sees two more doubles of herself sitting at a table. In turn each one picks up the key and it disappears and reappears back on the table, until one of the duplicate woman turns her hand over to reveal a darkened hand (blood?) holding the key, which turns into the knife. The man arrives carrying the big flower and they go to the bedroom where he strokes her, and she breaks the mirror of his face. Mirror fragments on the beach. Waves. The man is coming up the street, enters, and sees the woman dead in her chair. The whole piece has a muted, anxious lyricism; Deren is dressed in the stylish garb of an early-1940s bohemian and has piles of curly hair and an intelligent and sensual face. Hammid looks like a handsome revolutionary sailor from an Eisenstein movie. “Serious” droning music was added some years later, composed by Deren’s next husband, Teiji Ito. There’s no way of explaining the film—like most surrealist pieces it gets its life from the tension between images, rather than from any explicable narrative or coherent pattern of symbolic meaning.

A thirteen-minute experimental film made in Los Angeles by Maya Deren (née Eleanora Derenkowsky) and Alexander Hammid. The film is an unusual hybrid of surrealism, Freudian symbol, and art photography—as if Martha Graham and Luis Bunuel had collaborated on a project with an accomplished photographer who’d just been given her first movie camera. Actually, Deren had really just purchased a 16mm Bolex camera, and she and Hammid shot the film together. There is no plot, naturally, for the images and sequences recur, sometimes with variations, as do the symbolic set-pieces. The woman sees a tall, hooded figure with a mirror instead of a face and she follows it out of her house and along a summer street. She enters a room, sees the figure carry a large flower up some stairs and drop it on the bed. Or she is at home asleep in a chair. The figure is walking away as she watches it—and herself following—from the window. She takes a key from her mouth. She finds a butcher knife and carries it around. She is asleep. She is running. She enters a room where she sees two more doubles of herself sitting at a table. In turn each one picks up the key and it disappears and reappears back on the table, until one of the duplicate woman turns her hand over to reveal a darkened hand (blood?) holding the key, which turns into the knife. The man arrives carrying the big flower and they go to the bedroom where he strokes her, and she breaks the mirror of his face. Mirror fragments on the beach. Waves. The man is coming up the street, enters, and sees the woman dead in her chair. The whole piece has a muted, anxious lyricism; Deren is dressed in the stylish garb of an early-1940s bohemian and has piles of curly hair and an intelligent and sensual face. Hammid looks like a handsome revolutionary sailor from an Eisenstein movie. “Serious” droning music was added some years later, composed by Deren’s next husband, Teiji Ito. There’s no way of explaining the film—like most surrealist pieces it gets its life from the tension between images, rather than from any explicable narrative or coherent pattern of symbolic meaning.

Two things—a Peter Sellers comedy, which is good enough in itself. Here he plays Aldo Vanucci, an Italian master criminal, with full Italian cinema shtick, first as a gangster, and then as an over-the-top director Federico Fabrizi (the parodic snipe at Fellini is right out front). Vanucci conceives a scheme to smuggle gold stolen in Egypt by the befezzed Egyptian Okra (Akim Tamiroff, ready to play any sort of exotic foreigner), under the cover of making a movie. To do so, he steals the production equipment from Vittorio de Sica, playing himself in a brilliant satiric setpiece: as Moses walks into the desert, the director, riding on a crane, cries out, “More sand! More sand in the desert!” The giant fans blow and dust envelops everything. When it clears, de Sica is sitting on the ground and every bit of equipment is gone. And then the production, in a tiny coastal village, is a breathtaking parody of neorealism, with all the villagers clamoring to play parts, the vagueness and phony existentialism of the director’s posturing, and the cheekbones of the starstruck police chief (Lando Buzzanca). "Fabrizi" lures a has-been romantic lead Tony Powell (Victor Mature) and casts his girlfriend "Gina Romantica" (Britt Ekland) to play the ingenue. So much of the film industry and film culture is satirized it's hard to keep up a list--the international crime caper (think Pink Panther, Topkapi, etc), the epic film, the greed of producers, the affected mannerisms of directors, the overblown egos of actors, the unthinking adulation of the public, the barely submerged longing in everyday people for admission to the world of movies, and more.

Two things—a Peter Sellers comedy, which is good enough in itself. Here he plays Aldo Vanucci, an Italian master criminal, with full Italian cinema shtick, first as a gangster, and then as an over-the-top director Federico Fabrizi (the parodic snipe at Fellini is right out front). Vanucci conceives a scheme to smuggle gold stolen in Egypt by the befezzed Egyptian Okra (Akim Tamiroff, ready to play any sort of exotic foreigner), under the cover of making a movie. To do so, he steals the production equipment from Vittorio de Sica, playing himself in a brilliant satiric setpiece: as Moses walks into the desert, the director, riding on a crane, cries out, “More sand! More sand in the desert!” The giant fans blow and dust envelops everything. When it clears, de Sica is sitting on the ground and every bit of equipment is gone. And then the production, in a tiny coastal village, is a breathtaking parody of neorealism, with all the villagers clamoring to play parts, the vagueness and phony existentialism of the director’s posturing, and the cheekbones of the starstruck police chief (Lando Buzzanca). "Fabrizi" lures a has-been romantic lead Tony Powell (Victor Mature) and casts his girlfriend "Gina Romantica" (Britt Ekland) to play the ingenue. So much of the film industry and film culture is satirized it's hard to keep up a list--the international crime caper (think Pink Panther, Topkapi, etc), the epic film, the greed of producers, the affected mannerisms of directors, the overblown egos of actors, the unthinking adulation of the public, the barely submerged longing in everyday people for admission to the world of movies, and more.

At the trial—because of course everything goes wrong and everybody is arrested—the prosecutor shows the film the gang shot while carrying out their scam. It's a grotesque jumble of random black & white footage, but a film critic in the courtroom leaps to his feet applauding, and is carried out of the courtroom crying out that it is a work of primitive genius. The story is by Neil Simon, the star turn is by Peter Sellers, but the parody is pure de Sica. And the movie's satirical richness startled me; I had no idea!

Robert Donat plays Pitt as a patriotic man of principle, hating war but recognizing the need to resist the French attempt to conquer the world, doing battle with the know-nothing anti-war opposition led by Charles James Fox (Robert Morley), and aided by loyal, good men of various sorts. Pitt gives up his private life and his health for the country. From the peril of the English people to the reluctance of government to face danger to the treacherous and greedy fulminations of a tyrant (Napoleon, played well but briefly by Herbert Lom)—this is really all a fable of the second world war. It’s an impressive work, fiction as much as history.

Robert Donat plays Pitt as a patriotic man of principle, hating war but recognizing the need to resist the French attempt to conquer the world, doing battle with the know-nothing anti-war opposition led by Charles James Fox (Robert Morley), and aided by loyal, good men of various sorts. Pitt gives up his private life and his health for the country. From the peril of the English people to the reluctance of government to face danger to the treacherous and greedy fulminations of a tyrant (Napoleon, played well but briefly by Herbert Lom)—this is really all a fable of the second world war. It’s an impressive work, fiction as much as history.

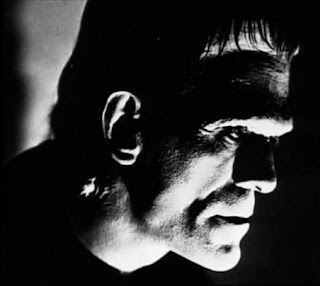

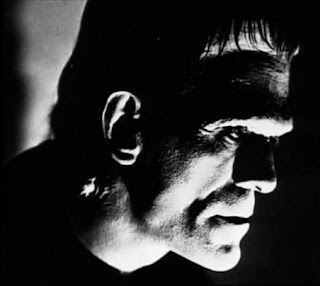

I. Frankenstein (James Whale,1932). Images from this movie are current in popular culture three-quarters of a century later. Whale manages to create shadowy black and white scenes of compelling, almost expressionist sharpness. Boris Karloff as the monster is hulking and impressive, and wholly creaturely—not a shred of humanity here, unlike the creation of the author here billed as “Mrs. Percy Shelley.” True, there is a little playfulness, and he likes children—though he throws little Maria into the lake after they run out of flower petals to throw. Colin Clive is the nervous doctor, whose impression of genius borders on the neurasthenic. He is only animated when he cries out, “It’s alive!” The monster dies in the fire that consumes the windmill where he takes refuge from the angry visitors.

I. Frankenstein (James Whale,1932). Images from this movie are current in popular culture three-quarters of a century later. Whale manages to create shadowy black and white scenes of compelling, almost expressionist sharpness. Boris Karloff as the monster is hulking and impressive, and wholly creaturely—not a shred of humanity here, unlike the creation of the author here billed as “Mrs. Percy Shelley.” True, there is a little playfulness, and he likes children—though he throws little Maria into the lake after they run out of flower petals to throw. Colin Clive is the nervous doctor, whose impression of genius borders on the neurasthenic. He is only animated when he cries out, “It’s alive!” The monster dies in the fire that consumes the windmill where he takes refuge from the angry visitors.

II. Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935): This sequel begins with a truly horrifying little skit: an overdressed trio of actors impersonating Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, and Lord Byron chat in an overdecorated drawing room while thunder rages outside the window. Byron (Gavin Gordon) limps slightly and rolls his Rs and waggles his eyebrows at Mary (Elsa Lanchester) flirtatiously. Mary allows that she has more stories to tell, and then this one starts right up. Henry Frankenstein is pursued by the ominous Dr. Pretorius (Ernst Thesiger) who has plans to make a female creature, and so he does. It’s Miss Lanchester, she of the electrical hair—but in fact she's really only in the movie for five minutes or so. A few tidbits from the original book occur here (the blind violinist). A comic role, Minnie the noisy maid, is added for Una O’Connor. The monster dies in the explosion in the tower.

II. Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935): This sequel begins with a truly horrifying little skit: an overdressed trio of actors impersonating Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, and Lord Byron chat in an overdecorated drawing room while thunder rages outside the window. Byron (Gavin Gordon) limps slightly and rolls his Rs and waggles his eyebrows at Mary (Elsa Lanchester) flirtatiously. Mary allows that she has more stories to tell, and then this one starts right up. Henry Frankenstein is pursued by the ominous Dr. Pretorius (Ernst Thesiger) who has plans to make a female creature, and so he does. It’s Miss Lanchester, she of the electrical hair—but in fact she's really only in the movie for five minutes or so. A few tidbits from the original book occur here (the blind violinist). A comic role, Minnie the noisy maid, is added for Una O’Connor. The monster dies in the explosion in the tower.

III. Son of Frankenstein (Rowland Lee, 1939): The monster (Karloff) is joined by Ygor (Bela Lugosi), who has befriended and taken over him, using him to kill the village jurors who previously had sentenced him (Ygor) to hang. They hide out in a stone dome laboratory, partly ruined. Lionel Atwil makes a good Inspector, complete with a prosthetic arm that locks in place and is almost as hard to control as Dr. Strangelove’s hand. Oh, and he stores his darts in the wooden arm. Eventually the monster dies in a pit of boiling sulphur.

III. Son of Frankenstein (Rowland Lee, 1939): The monster (Karloff) is joined by Ygor (Bela Lugosi), who has befriended and taken over him, using him to kill the village jurors who previously had sentenced him (Ygor) to hang. They hide out in a stone dome laboratory, partly ruined. Lionel Atwil makes a good Inspector, complete with a prosthetic arm that locks in place and is almost as hard to control as Dr. Strangelove’s hand. Oh, and he stores his darts in the wooden arm. Eventually the monster dies in a pit of boiling sulphur.

IV. The Ghost of Frankenstein (Earl C. Kenton, 1942): The fourth of the early series, this time straying farther and farther afield--this could be one of the first major B-movie franchises, and Karloff was not invited to the party. It turns out that Dr. Heinrich Frankenstein had a brother, Ludwig (Cedric Hardwicke), who is an eminent psychiatrist with tired-looking eyes, a frustrated assistant, and a pretty daughter. Ygor, the assistant (Bela Lugosi) digs up the monster (Lon Chaney) out of the sulphur pit and goes to the hospital, where he plans to have his own brain transplanted into the monster's skull. Then it's alive. I forget how the monster dies this time.

IV. The Ghost of Frankenstein (Earl C. Kenton, 1942): The fourth of the early series, this time straying farther and farther afield--this could be one of the first major B-movie franchises, and Karloff was not invited to the party. It turns out that Dr. Heinrich Frankenstein had a brother, Ludwig (Cedric Hardwicke), who is an eminent psychiatrist with tired-looking eyes, a frustrated assistant, and a pretty daughter. Ygor, the assistant (Bela Lugosi) digs up the monster (Lon Chaney) out of the sulphur pit and goes to the hospital, where he plans to have his own brain transplanted into the monster's skull. Then it's alive. I forget how the monster dies this time.

V. Frankenstein meets the Wolfman (Roy William Neill, 1943): What a great idea! Let the stars of two spooky franchise work together, sort of like a scary Hope and Crosby on the Road to Transylvania. Poor Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.), brokenhearted lycanthrope, chips the monster (Bela Lugosi) out of a giant block of ice. Perhaps to justify Lugosi's exotic accent, the location has shifted mysteriously to a small central European country of Vasalia, home of Castle Frankenstein, where the Countess Frankestein (Ilona Massey). Some of the cast from the Wolfman have strayed onto the set, notably the old gypsy fortuneteller Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya). The monster dies again in the end, of course.

V. Frankenstein meets the Wolfman (Roy William Neill, 1943): What a great idea! Let the stars of two spooky franchise work together, sort of like a scary Hope and Crosby on the Road to Transylvania. Poor Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.), brokenhearted lycanthrope, chips the monster (Bela Lugosi) out of a giant block of ice. Perhaps to justify Lugosi's exotic accent, the location has shifted mysteriously to a small central European country of Vasalia, home of Castle Frankenstein, where the Countess Frankestein (Ilona Massey). Some of the cast from the Wolfman have strayed onto the set, notably the old gypsy fortuneteller Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya). The monster dies again in the end, of course.

VI. House of Frankenstein (Erle C. Kenton, 1944). It's a party and everybody's invited! The wolfman returns, played by Lon Chaney as a sad, cursed soul longing for the release promised by the evil Dr. Niemann (Boris Karloff) and his hunchbacked assistant Daniel (J. Carroll Naish), in love with the gypsy girl Ilonka (Elena Verdugo), also the object of Daniel’s fruitless passion. Escaping from an asylum after a terrific thunderstorm, Niemann and Daniel take over a travelling show of horrors after killing the proprietor, and reawaken Dracula (John Carradine), who moves about menacingly, opens his eyes wide, and becomes a badly-animated bat, but then he disappears from the plot fairly early. Some of the same minor players from earlier movies appear, notably Leonard Atwill and Sig Ruman, but the movie is noteworthy for its complete embodiment of the generic horror story with a cast of, well, dozens. It’s fascinating to see two ex-monsters in human guise; the monster is played by an extra and has very little to do except die in the last minutes of the movie, this time in quicksand.

VI. House of Frankenstein (Erle C. Kenton, 1944). It's a party and everybody's invited! The wolfman returns, played by Lon Chaney as a sad, cursed soul longing for the release promised by the evil Dr. Niemann (Boris Karloff) and his hunchbacked assistant Daniel (J. Carroll Naish), in love with the gypsy girl Ilonka (Elena Verdugo), also the object of Daniel’s fruitless passion. Escaping from an asylum after a terrific thunderstorm, Niemann and Daniel take over a travelling show of horrors after killing the proprietor, and reawaken Dracula (John Carradine), who moves about menacingly, opens his eyes wide, and becomes a badly-animated bat, but then he disappears from the plot fairly early. Some of the same minor players from earlier movies appear, notably Leonard Atwill and Sig Ruman, but the movie is noteworthy for its complete embodiment of the generic horror story with a cast of, well, dozens. It’s fascinating to see two ex-monsters in human guise; the monster is played by an extra and has very little to do except die in the last minutes of the movie, this time in quicksand.

This would be a very interesting movie to study as a case of synthesis in film-making. A number of sets were made on the back lots and on location in California—some of the trees are recognizably California trees, perhaps the Eucalyptus imported from the Antipodes long ago. And then they use lots of stock footage shot in Africa, and perhaps a bit shot in zoos as well, mixed up with footage of trained (circus) animals. In the early part of the movie the actors perform in front of location shots, back-projected film of Africans in traditional costume, gathering and drumming and dancing. The actors walk around the corner of a bamboo house and stand in front of the people supposedly gathered for trading. In other scenes there is often intelligent intercutting between animal footage and live action—real alligators hurry toward the water and swim amongst real hippos, and then the editor cuts to a safe pond where mechanical crocodile backs churn across the surface in perfect coordination, like water ballet, as Johnny Weismuller swims steadily away from them his championship crawl. The mixture of actual apes (chimpanzees) and people in ape costume is perhaps the least convincing blend. The story is rather dim and missing key elements of continuity, but it doesn’t seem to matter so much, since the main point of the film is to bring Tarzan and Jane (Maureen O’Sullivan) together. There’s a crusty father (C. Aubrey Smith) determined to find the elephants’ graveyard, and a stalwart colonial hero, Henry Holt (Neil Hamilton) who begins well but goes downhill as the trek through the jungle shows him to be a brute, and there are perhaps a dozen expendable black porters, killed along the way by falls from cliffs, arrows of hostile tribes, crocodile teeth, and some sort of captive gorilla-god. There aren’t any left at the end of the trip, though all the white people survive. This isn’t good. Weirdest of all is the appearance of the hostile tribe—they’re not pygmies, they’re dwarfs, as the father explains in matter-of-fact tones. Sure enough, it’s the entire stock of Hollywood small people in blackface make-up. Tarzan and the friendly elephants take care of them. What is decidedly not pleasant here is the explicit racism, the profiteering and imperialist motives, and the callousness toward African human and animal life. Even Tarzan is guilty, for he dispatches several of the porters himself after Holt has shot one of his ape-friends. Jane tries to prevent Holt from shooting Tarzan by crying out, “He’s White!” Not so much, according to the father, who deems Tarzan little more than an animal, and Holt sneers and glowers. And well he might, because he’d imagined Jane was his property. There’s the other fascinating thing about this movie: the attraction between the nearly-mute, beautiful ape-man and the nearly-always-speaking, beautiful “civilized” girl. It can’t be anything but animal magnetism, or, rather, pure sex. Weismuller spends the whole film nearly naked, and looking pretty good, and O’Sullivan indicates her potential sexiness when she changes clothes early in the film, pausing in her silky undergarments to laugh at her father’s discomfiture. By the time her clothes get torn and she goes swimming with Tarzan, her curves and general loveliness become an integral part of the story. Tarzan and Jane are fascinated by each other, and can’t stop staring. Tarzan is curious and innocent and hypnotized, and Jane passes through the obligatory stage of being frightened into an appreciation of Tarzan’s character, beauty, and sense of identity in and with the jungle, and at last into a happy ease in her own sensuality. This last development allows her to stay in Africa as Holt retreats on the back of a borrowed elephant. This is a ridiculous and offensive movie, and it is also rather wonderful. The best moment, other than O’Sullivan and Weismuller at play in the water and all wet on shore, is when Jane is bandaging the wounded Tarzan’s head and the young chimpanzee puts his arm familiarly around her shoulders.

This would be a very interesting movie to study as a case of synthesis in film-making. A number of sets were made on the back lots and on location in California—some of the trees are recognizably California trees, perhaps the Eucalyptus imported from the Antipodes long ago. And then they use lots of stock footage shot in Africa, and perhaps a bit shot in zoos as well, mixed up with footage of trained (circus) animals. In the early part of the movie the actors perform in front of location shots, back-projected film of Africans in traditional costume, gathering and drumming and dancing. The actors walk around the corner of a bamboo house and stand in front of the people supposedly gathered for trading. In other scenes there is often intelligent intercutting between animal footage and live action—real alligators hurry toward the water and swim amongst real hippos, and then the editor cuts to a safe pond where mechanical crocodile backs churn across the surface in perfect coordination, like water ballet, as Johnny Weismuller swims steadily away from them his championship crawl. The mixture of actual apes (chimpanzees) and people in ape costume is perhaps the least convincing blend. The story is rather dim and missing key elements of continuity, but it doesn’t seem to matter so much, since the main point of the film is to bring Tarzan and Jane (Maureen O’Sullivan) together. There’s a crusty father (C. Aubrey Smith) determined to find the elephants’ graveyard, and a stalwart colonial hero, Henry Holt (Neil Hamilton) who begins well but goes downhill as the trek through the jungle shows him to be a brute, and there are perhaps a dozen expendable black porters, killed along the way by falls from cliffs, arrows of hostile tribes, crocodile teeth, and some sort of captive gorilla-god. There aren’t any left at the end of the trip, though all the white people survive. This isn’t good. Weirdest of all is the appearance of the hostile tribe—they’re not pygmies, they’re dwarfs, as the father explains in matter-of-fact tones. Sure enough, it’s the entire stock of Hollywood small people in blackface make-up. Tarzan and the friendly elephants take care of them. What is decidedly not pleasant here is the explicit racism, the profiteering and imperialist motives, and the callousness toward African human and animal life. Even Tarzan is guilty, for he dispatches several of the porters himself after Holt has shot one of his ape-friends. Jane tries to prevent Holt from shooting Tarzan by crying out, “He’s White!” Not so much, according to the father, who deems Tarzan little more than an animal, and Holt sneers and glowers. And well he might, because he’d imagined Jane was his property. There’s the other fascinating thing about this movie: the attraction between the nearly-mute, beautiful ape-man and the nearly-always-speaking, beautiful “civilized” girl. It can’t be anything but animal magnetism, or, rather, pure sex. Weismuller spends the whole film nearly naked, and looking pretty good, and O’Sullivan indicates her potential sexiness when she changes clothes early in the film, pausing in her silky undergarments to laugh at her father’s discomfiture. By the time her clothes get torn and she goes swimming with Tarzan, her curves and general loveliness become an integral part of the story. Tarzan and Jane are fascinated by each other, and can’t stop staring. Tarzan is curious and innocent and hypnotized, and Jane passes through the obligatory stage of being frightened into an appreciation of Tarzan’s character, beauty, and sense of identity in and with the jungle, and at last into a happy ease in her own sensuality. This last development allows her to stay in Africa as Holt retreats on the back of a borrowed elephant. This is a ridiculous and offensive movie, and it is also rather wonderful. The best moment, other than O’Sullivan and Weismuller at play in the water and all wet on shore, is when Jane is bandaging the wounded Tarzan’s head and the young chimpanzee puts his arm familiarly around her shoulders.

This film seems to occupy a zone at the borders of a lot of different genres. Of course it is a vampire movie, complete with an ancient creature, Marguerite Chopin, with dark powers, corrupted minions, pale and suffering female victims, and an earnest young man appalled but also fascinated. In this instance the well dressed young man Allan Gray (Julian West)—he’s always wearing a tie—arrives as things are falling apart. Fueled by a sense of dread, as the intertitles inform us, Allan wanders all over the manor on the bright moonlit nights. He sees the shadows of people digging, arguing, and dancing, he sees disturbing glimpses of ominous things, and even the ordinary things about the place take on a tone of ominousness. At one point he becomes insubstantial, his transparent hand opening a door. He sees himself in a coffin with a little window, and then we see as he would see from inside, the peg-legged soldier screwing down the lid, the vampire peering in, a candle burning and melting. There are scenes of chasing, of rowing a boat in the fog, of Allan staring incredulously at the dying father, the anemic daughter, the manifold strangenesses—all this suggests the work of Man Ray and people like that, rather than than a traditional vampire narrative. After reading the book the father has left behind for Allan, the elderly handyman goes off to the churchyard to drive a stake through the monster's heart, and Allan helps. The body in the coffin turns to bones, the peg-legged soldier falls downstairs, the wicked doctor is suffocated with flour in the mill, the anemic woman is revived, and her young, wide-eyed sister and Allan go running through the woods toward the light –the emblematic happy ending. A goo

This film seems to occupy a zone at the borders of a lot of different genres. Of course it is a vampire movie, complete with an ancient creature, Marguerite Chopin, with dark powers, corrupted minions, pale and suffering female victims, and an earnest young man appalled but also fascinated. In this instance the well dressed young man Allan Gray (Julian West)—he’s always wearing a tie—arrives as things are falling apart. Fueled by a sense of dread, as the intertitles inform us, Allan wanders all over the manor on the bright moonlit nights. He sees the shadows of people digging, arguing, and dancing, he sees disturbing glimpses of ominous things, and even the ordinary things about the place take on a tone of ominousness. At one point he becomes insubstantial, his transparent hand opening a door. He sees himself in a coffin with a little window, and then we see as he would see from inside, the peg-legged soldier screwing down the lid, the vampire peering in, a candle burning and melting. There are scenes of chasing, of rowing a boat in the fog, of Allan staring incredulously at the dying father, the anemic daughter, the manifold strangenesses—all this suggests the work of Man Ray and people like that, rather than than a traditional vampire narrative. After reading the book the father has left behind for Allan, the elderly handyman goes off to the churchyard to drive a stake through the monster's heart, and Allan helps. The body in the coffin turns to bones, the peg-legged soldier falls downstairs, the wicked doctor is suffocated with flour in the mill, the anemic woman is revived, and her young, wide-eyed sister and Allan go running through the woods toward the light –the emblematic happy ending. A goo d deal of the film is beautifully shot, using experimental techniques. Another odd thing is that the film has a sound track, with scary music and sounds, but there’s not a lot of talking and a lot of scenes involve lengthy close-ups of faces changing expression, and so it feels a lot like a silent film. And because so much of the film is mediated through Allan, whose dream it is, there’s not really so much scariness.

d deal of the film is beautifully shot, using experimental techniques. Another odd thing is that the film has a sound track, with scary music and sounds, but there’s not a lot of talking and a lot of scenes involve lengthy close-ups of faces changing expression, and so it feels a lot like a silent film. And because so much of the film is mediated through Allan, whose dream it is, there’s not really so much scariness.